Breathing Easier During COVID-19: Hyperbaric Hoods in the ICU

By: Michael Harrison, MD, PhD, MPH; Devang Sanghavi, MD, MHA, FCCP; Klaus Torp, MD; Jorge Mallea, MD; and Pablo Moreno Franco, MD, FCCP

October 1, 2020

Mayo Clinic Jacksonville is a destination medical center that specializes in solid organ and bone marrow transplants. Our patients on any given day are the definition of those most vulnerable to an infectious disease. From the outset, we knew the COVID-19 pandemic was going to present challenges to how we treated our patients in the intensive care unit (ICU). Our personal and professional interactions with our colleagues at other institutions highlighted one area of significant concern—respiratory support for critically ill patients. What are the criteria for intubation? Is early intubation for hypoxia an invitation for adverse outcomes? Will we have enough ventilators? Will we have enough staff? Will we have enough sedative medications? And how could we maximize the resources we did have?

The solution seemed easy—obtain more vents and train people to operate them. Our staff collaborated with private industry to design a ventilator that could be made using automotive parts. However, this solution would require time and significant resources and did not address the risk associated with early intubation for “happy hypoxia.” Creative thinking, however, led to a cheap and easy, off-the-shelf solution that helped prevent the need for intubation purely for hypoxia. We ordered hyperbaric hoods, even though we do not have a hyperbaric chamber at Mayo Clinic Jacksonville.

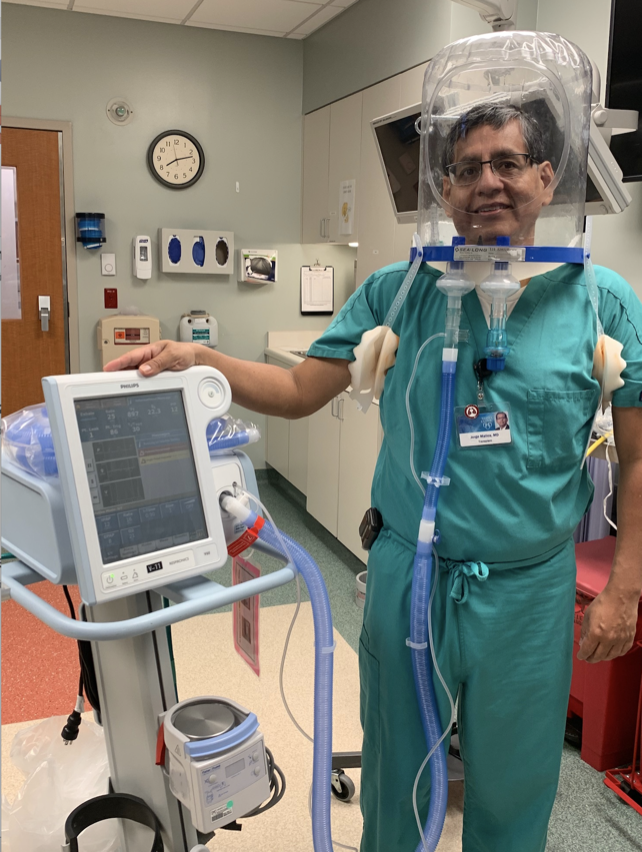

Jorge Mallea, MD, demonstrates the use of a hyperbaric oxygen hood.

Jorge Mallea, MD, demonstrates the use of a hyperbaric oxygen hood.

Hyperbaric hoods are large, clear, vinyl coverings that go over the patient’s head. A latex ring goes around the patient’s neck and creates an airtight seal inside the hood. The patient’s respiration occurs in the small volume within the hood, and it is possible to create an atmosphere of 100% oxygen. Our patients describe this as more comfortable than other oxygen delivery methods, such as nasal cannula, high-flow nasal cannula, or positive pressure ventilation. The helmet could be donned and doffed with ease, and the patients were able to take short breaks to eat and drink as tolerated. Additional support, such as the delivery of nitric oxide for pulmonary vasodilation, could be provided through the hood.

We used this approach as much as we could, and we were surprised with the outcomes. We were successful in delaying or preventing intubation in a number of cases. The hood alleviated the work of breathing, treated hypoxia, and did not present the same risks associated with intubation (eg, ventilator-associated pneumonia), noninvasive ventilation (eg, skin breakdown on bridge of nose, challenges with providing enteral nutrition), or other forms of respiratory support. Most importantly, the solution was extremely cost-effective—approximately $200 per unit.

During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, we had a number of innovative solutions to provide optimal patient care at Mayo Clinic. We were the one of the first hospitals in the country to test all the patients who were admitted to the hospital or who came for an elective procedure. We relocated the ventilator consoles, IV pumps, and continuous renal replacement therapy machines outside the patient’s room—simple adjustments to settings and silencing alarms no longer required PPE and carried the ever-present risk of exposure. We began to save used PPE, such as N95 masks, and investigate the best ways to disinfect them without affecting their filtering integrity.

However, the use of the hyperbaric hood—medical equipment commonly used for the outpatient treatment of chronic wounds—may have had the biggest impact on our patient care. It was safe, cost-effective, and did not require additional resources or training to implement. More importantly, it helped our critically ill patients. That made everyone breathe just a little easier.

Michael Harrison, MD, PhD, MPH, is a Senior Associate Consultant in the Department of Critical Care and Emergency Medicine at Mayo Clinic Florida.

Devang Sanghavi, MD, MHA, FCCP, is the Director of the Medical Intensive Care Unit at Mayo Clinic Florida.

Klaus Torp, MD, is a Consultant in the Department of Anesthesiology at Mayo Clinic Florida.

Jorge Mallea, MD, is a Consultant in the Department of Pulmonary Medicine at Mayo Clinic Florida.

Pablo Moreno Franco, MD, FCCP, is the Chairman of the Department of Critical Care Medicine at Mayo Clinic Florida.